- South Africa’s water infrastructure is deteriorating, with the Department of Water and Sanitation estimating the country needs to spend over R90 billion a year over the next decade to repair and upgrade existing infrastructure, a clear indicator of the scale of the problem.

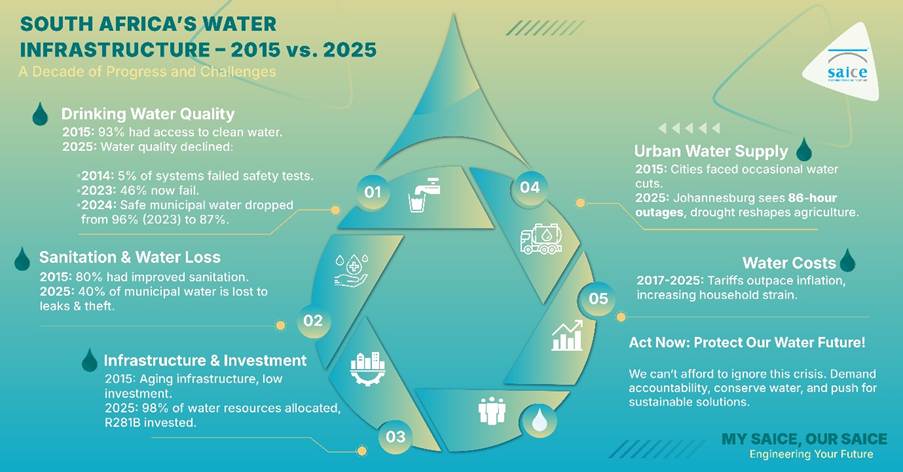

- The SAICE Water Division comments that “over 40% of the proportion of water produced and supplied for more than 80% of the country, is lost due to insufficiently maintained infrastructure resulting in high non-revenue water (NRW) due to leaks, commercial losses such as meter under-readings or theft”.

- The government has secured R23-billion for seven large water infrastructure projects, recognising the urgency of the situation, but SAICE water experts say this is just a drop in the ocean for what is genuinely needed to stem South Africa’s water crises.

South Africa stands at a critical juncture in its infrastructure development, with water infrastructure at the forefront of this challenge. Water security is the foundation of economic stability and growth. Without reliable access to clean and affordable water, industries falter, agriculture suffers, communities struggle and investors reconsider investment in South Africa. From Nelson Mandela Bay and Komani in the Eastern Cape to the unfolding water shortages in Johannesburg, Gauteng, millions of South Africans are grappling with dry taps, unreliable supply, and deteriorating infrastructure.

For millions living in poverty, unreliable access to clean water is not just an inconvenience. It poses a daily threat to health, livelihoods, and survival, not to mention revoking the constitutional human right to water, as enshrined as a fundamental human right in South Africa (supported by both the Constitution of 1996 and the Water Services Act 108 of 1997). Water insecurity has a ripple effect, with a potential of slowing the economy, disrupting education, worsening food shortages and undermining the country’s overall stability.

Despite the R156.3-billion being committed towards water and sanitation in the recent 2025 budget speech, it is understandable that water engineering experts from the South African Institution of Civil Engineering (SAICE) are justifiably concerned that the municipalities might lack the engineering expertise among other things to use these grants efficiently.

As Water month in South Africa has come and gone, with the celebrated World Water Day on 22 March 2025, we are keenly reminded of the harsh reality that South Africa is a water-scarce country, relying on only about half of the global average rainfall to replenish our surface water sources.

So, what is the cost of inaction in terms of water security for South Africa?

The country’s water infrastructure crisis has been exacerbated by rapid population growth and urbanization, climate change, inefficient water management, poorly maintained infrastructure, and unequal distribution of water resources. Inadequate investment in water infrastructure – specifically underfunding of operations and maintenance – along with increasing water resource scarcity, have emerged as further major challenges. Solving them is not just an environmental necessity but an economic imperative. The fact is, without adequate water security, our economy will contract.

Despite the R156.3-billion being committed towards water and sanitation in the recent 2025 budget speech, it is understandable that water engineering experts from the South African Institution of Civil Engineering (SAICE) are justifiably concerned that the municipalities might lack the engineering expertise among other things to use these grants efficiently.

“In the absence of proper planning, feasibility studies and suitable technically driven procurement, such grants may be misspent or even unspent whether on upgrading, renewal or new infrastructure,” comments Wynand Dreyer, Chair of the SAICE Advocacy Committee.

The SAICE Water Division acknowledges the positive strides made by the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) in recent years. In his budget speech on 16 July 2024, Honourable David Mahlobo, Deputy Minister of DWS, highlighted that nearly R98 billion has been spent by the department to support municipalities in infrastructure development across 144 Water Service Authorities. This significant commitment to improving water infrastructure is encouraging, and SAICE fully supports these efforts.

However, although there are some encouraging developments, SAICE cautions that there are still serious challenges that need to be overcome. One only has to take a look at recent history: between 2018 and 2022, expenditure at the DWS hovered between R17 billion for all water programmes, including new projects and maintenance. In contrast the budget for the 2023 to 2025 period of R69.3 billion in total failed to make a dent, falling R200 billion short of the necessary target.

“The imperative to fix and renew aged and defective infrastructure cannot be overemphasised. Our statistics on non-revenue water tell a damning story of neglect with over 40% of water produced and supplied to more than 80% of the country, lost due to aging and broken infrastructure as a result of leaks or unaccounted for water due to theft. We desperately need to see these numbers turned around,” emphasises Dreyer.

Environmentally, dysfunctional wastewater treatment plants have played a significant role in untreated, or partially treated, sewage being discharged into the environment, including rivers and oceans. Lack of compliance and monitoring by competent authorities exacerbates the water crises. During minor floods, the impact of the degraded water flow into rivers is huge, with wastewater treatment plants discharges stimulating excessive reed growth, which in turn, alters riverbeds. The result is that instead of there being a 1:50 or 1:100 year chance of floods, developments in areas that were previously far away from the flood zones, now fall within these flood zones, increasing their risk of being flooded.

“This is detrimental to the environment as it pollutes the watercourses from which we abstract our drinking water, adding to the complexity and cost of purification, pollutes our oceans, and is, in turn, hazardous to our health and the seafood we eat. Not to mention exposing the risk of floods to many developments which previously were not at risk,” explains the Water Division.

Turning focus to spatial planning and developments, the increasing demand for inner city accommodation as a result of migration of people to urban areas requires the planning of serviced human settlements in appropriate areas. Engineers need to be involved or at least contribute towards these developments. There is no denying the effect of failure of many municipal governments to maintain and enhance their infrastructure, in the face of increasing demand by growing inner city populations.

“This situation requires holistic project management and implementation setup to ensure the project cycle can be used to contribute to success in restoring aging or collapsed infrastructure, plan better and operate the system properly. If the system is not robust, corruption, theft and vandalism remain the cancer of the system,” notes Segomotso Kelefetswe, SAICE’s advocacy contributor on water infrastructure.

“A sphere of government needs to be encouraged to appoint properly qualified and professionally registered personnel with reputable track record or appoint a panel of experts to support the implementation, training and development with the eye to improve skill (capacity building) and also ability to retain the talent,” adds Kelefetswe.

Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) have the potential to bridge the skills gap but only if the initial project preparation i.e. the feasibility studies and PPP procurement process, is properly done by the municipality, with specialist assistance where required. PPPs hold the promise of leveraging limited government funding to crowd in project finance for bankable projects, along with the PPP Unit and GTAC in National Treasury both providing free advisory support for such initiatives and the DBSA and ISA both indicating their willingness to support project preparation with qualified personnel and seed capital.

Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) have the potential to bridge the skills gap but only if the initial project preparation i.e. the feasibility studies and PPP procurement process, is properly done by the municipality, with specialist assistance where required.

When a PPP is concluded, the procuring state entity has the assurance of efficient construction and a robust contract and budget to maintain the facility for 20 years at least. The cost however has to be covered through the tariff and must be properly considered during feasibility.

Says Dreyer, “SAICE has identified experienced engineering personnel who are willing and able to take on short-term assignments to add capacity to these initiatives and also has wide-ranging learning programmes aimed at up-skilling engineering personnel in metros and municipalities. Many of these programmes are accessible online and through self-study.”

Shares Kelefetswe, “There are entities that have started to put in action a deliberate intention to encourage the public sector to support the government as part of ensuring that planned programmes do get to fruition. The process involves PPP but in a collaborative style as the Private Sector and Public sector co-implement projects at a shared responsibility level, and we use a 50-50% split in terms of overall responsibility inclusive of management, funding contribution, implementation and further processes that even extend to municipal readiness.”

“It would be good to work towards various PPPs in a collaborative manner, allowing the parties to work through a signed agreement to ensure we save time and cost. Secondly, funds allocated to projects in most systems goes towards the projects plus other costs, yet in collaboration setup, the full cost goes to the project as in Rand for Rand and that optimises the amount of money to be spent on the project. Thirdly, institutional arrangement must uphold the public procurement system with transparency, ethics and accountability as key cornerstones,” advises Kelefetswe.

“The optimal solution needs to be held at an institutional level with the amount of money lost or stolen being reduced. That is the only way the funds will get to do what it was originally intended,” adds Kelefetswe.

Looking forward, leadership both nationally and on a municipal level need to be informed and influenced to make the appropriate decisions on policy, budgeting and priorities around water resource management and development, to avert this looming water security crisis.

For more information, visit https://saice.org.za